Cash Boot Camp for Treasurers

Introduction

Successful Treasurers take decisive ownership of cash for their organization and decide how cash is kept, controlled, managed, and moved. However, he or she is not on an island and must share reporting and recording details of cash with colleagues from other departments, many of whom will have differing cash viewpoints. At first glance, a Treasurer’s view of cash can seem discordant to those outside of Treasury. It is important for the Treasurer to understand the Treasury view of cash as well as the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) view of cash, which is typically held by the Controller and the Accounting department. The good news is that it is possible to record and report on cash in a manner that complies with accounting principles and provides a better, more controlled process.

GAAP Cash and Treasury Cash

GAAP cash can be thought of as cash from a reporting standpoint. It essentially ignores the concept of float—the idea that it takes time to settle a financial transaction in your bank account. The time a check is deposited and the moment when funds are made available is viewed as imminent, and any delays to this process are not taken into consideration. Thus, typical cash reporting to meet GAAP requirements results in “the books” not reflecting actual bank activity.

On the other hand, Treasury’s view of cash (aka, real cash) differs from the traditional accounting view of cash or GAAP cash. Treasury is concerned with liquidity management (cash, short-term debt and investments, and several other current asset and liability items), which means they must reduce borrowing costs and optimize investment earnings. The amount of float for funds disbursed and received can be substantial (tens of millions of dollars) and the Treasurer must take advantage of cash management tools to optimize these funds. Disbursement float can be invested or used to pay debt. The idea of leaving excess balances in a checking account to cover all balances, while safe, is outdated and inefficient compared to other opportunities.

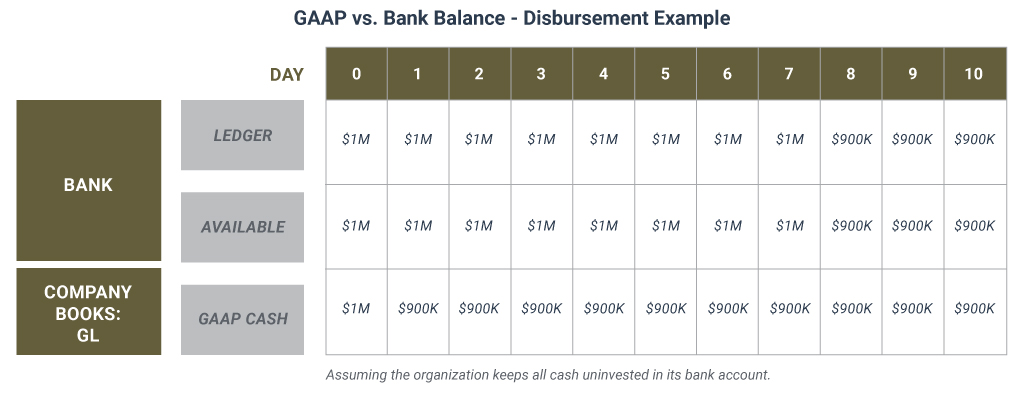

DISBURSEMENT EXAMPLE

Let’s imagine an organization issues a $100,000 check to buy an asset, and, of course, accounting entries are made accordingly—accounting deducts the purchase from the company books. That asset has been received, and although the $100,000 check has not cleared, accounting has recorded the transaction. On Day 8 when the check clears for the purchase, no changes are made to the balance sheet because the accounting entry has already been recorded. Thus, the clearing of the check really has no meaning for reporting purposes. But, for the one week where the funds had yet to clear, $100,000 was available for treasury ledger to make investment, borrowing, or forecasting decisions—there is no indication of what disbursement float exists. It can be difficult to distinguish accounting cash and usable cash. The difference can lead to extra work for both parties when it comes to formal bank reconciliation and other variance analysis activities. The following diagram shows how cash is viewed through different lenses during disbursement.

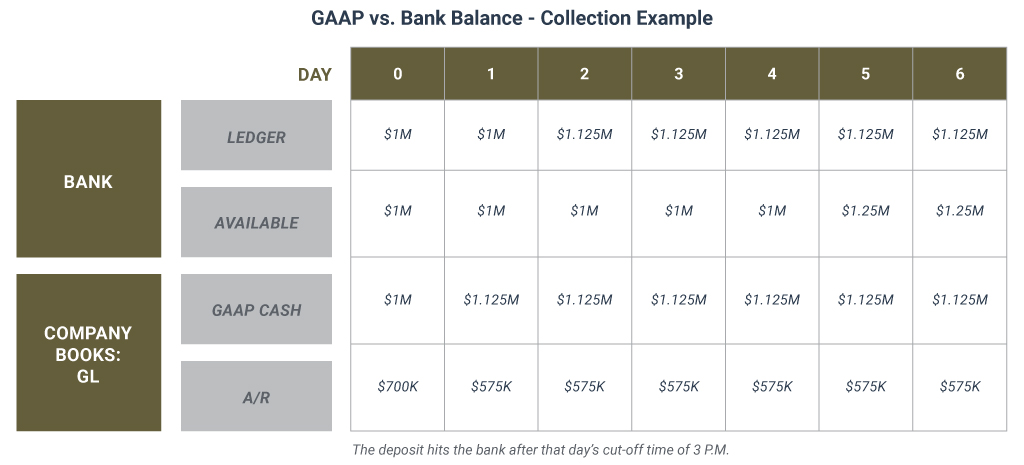

COLLECTION EXAMPLE

Suppose a $125,000 check is received in your organization’s lock box (Day 1) and the company books (A/R and then GAAP cash) are updated. The $125,000 received, while recorded and listed on the balance sheet, cannot be invested because the funds have not cleared. Despite this, the Treasurer may be asked: Why aren’t the full funds (according to the ledger) being invested? Treasury must wait until Day 5 when the funds were made available and can now be used. The diagram below illustrates the discrepancy between the bank and the Company ledger.

DISCUSSION

GAAP requirements for reporting do not completely rule out the use of more accurate or legitimate recording methods. Instead, it is possible to track float and separately track various liabilities for the benefit of Treasury. If implemented, this type of reporting workflow would benefit the Controller’s function while also supporting good treasury practices. Today, the best way to employ these workflows is through the use of technology.

TECHNOLOGY

It is critical to record cash in the general ledger in a way that is useful to the Treasurer but that also complies with GAAP. In cases where technology can be used to automate the entry-posting process, allowing treasury to add “cash-clearing” entries to the general ledger will make it easier for all parties to identify current cash positions and balances, while still meeting GAAP. Automated recording allows this segregation of duties to exist because:

- Treasury records all cash in an automated manner

- Operating areas record their subledger directly

- Bank reconciliation is simplified as bank transactions are recorded and matched quickly

- Subledger reconciliation is far simpler

- It supports an efficient design for the bank system for Treasury purposes

- It supports the accounting needs and strengthens them through a clear segregation of duties

CASH IMPLICATION

Cash from a Treasury perspective vs. cash from accounting perspective can be very different. Just because an organization has cash available under GAAP reporting does not mean those funds can be invested or used to pay bills. This situation can be avoided by allowing for the distinction between funds that are available for use and those funds that are not available by recording those initial entries against a cash-clearing account.

THREE KEY CONCEPTS:

- Cash is viewed in a different light by treasurers compared to other departments internally.

- However, Treasury’s cash reporting needs can still be addressed in a manner fully compliant with GAAP reporting.

- Adopting an improvised cash reporting workflow that accounts for float and other processing delays provides for better controls and improved information in the financial records of the organization, which serves to benefit all parties.

Jessica Terrien Dunn

Content Analyst

Jessica Terrien Dunn works as a content analyst and coordinates SecureTreasury, the corporate training program, in the market intelligence division of Strategic Treasurer, a top tier treasury consultancy headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia.